Addressing Anti-Blackness in the Desi Community

“Kalo jogoter alo.” We say it, but why do we preach otherwise?

There have been more than one instance where I heard a relative say “kalo ra kintu bhalo na.” Or use the term “kalaiya” in a derogatory way. We’ve all heard it. Be it our mama or chacha or even sometimes a cousin our age.

This is blatant racism.

Sometimes it happens in a room full of Bengali people, chatting while munching over chaa and shingara… or sometimes subtly, when a Bengali person shifts on his or her seat as a black person sits next to them on public transport. It happens when young Bangladeshis use the n-word, even after knowing the context behind it. It happens when our parents warn us not to mix with black kids. Where there is public praise of the first black president of the United States, or Muhammad Ali beacuse he’s Muslim, there is privately shaming black people in bodegas or cursing them while driving. But why this dichotomy, this hypocrisy? What gives us this entitlement? We have had our fair share of being discriminated against for our brown skin, even in a city as diverse as New York…so why is it that some of us treat our fellow POC (People of color) brothers and sisters as if we are somehow better?

This is blatant racism, and I’m calling it out.

Anti-blackness in the Bengali community definitely has its roots in colorism in the Bengali mindset. We discriminate within our own race, against Bengalis who are darker skinned. This comes to light in instances like when elders look for a bride or groom for their kids, and “forsha” (light-skinned) becomes a requirement. When we use words like “gayer rong moila” for people with dark skin. Dark means dirty to many Bengalis; it is sickening.

Anti-blackness in the Bengali community could also be attributed to the negative light the media unfairly has shone on black people, the nasty stereotype that African Americans tend to be “dangerous.” This kind of narrow minded thinking seems to line perfectly parallel to those of white supremacists, and our own past colonizers: the British. How did we end up finding ourselves having a mindset that aligns with those that we ourselves claim to condemn?

Paulo Friere discusses in his book, “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” that, “The oppressed, instead of striving for liberation, tend themselves to become oppressors.” In our attempt to overcompensate for our past dehumanization, we have become arrogant towards others, and in many ways, adopted the behaviors of our past oppressors, i.e british colonizers.

Amar bhai er rokte rangano ekushe february. Ami ki bhulite pari.

How quickly we forget, that not too long ago we were a people who also had to fight for freedom and liberation, for the right to speak our own language. Post-liberation, we have become, or probably just remained, a people that criticizes others and puts them down because of their dark skin tone.

Post liberation, our parents’ generation tried to overcompensate for their feelings of being “less than” by becoming lawyers and doctors, and engineers, and even tried to force a lot of us to take on these paths regardless of our own choices. With this, I’ve noticed, there came a lot of arrogance, and not to mention, the model minority myth, that somehow, because we have a high number of doctors and lawyers in our race, we must be better than minorities in this country. We choose to feel superior to African Americans because of their high crime rate instead of educating ourselves about the fact that those high numbers are due to the prejudice and brutality they face in the hands of police in this country. We need to acknowledge the unfair judicial system that disproportionately locks up young black men in jail.

I have black friends who are ten times smarter, and ten times more hard working, and ten times more successful than me or my Bengali counterparts. And I am all for it. I know these conversations are uncomfortable to have with some of our elders, who walk around unknowingly being racist. We were always taught to respect our elders; it becomes difficult to speak against them when they make blatantly racist remarks. I am on a quest myself, to find out ways to talk about these things openly. I urge all my Bengali friends to take on some of the burden off our black brothers and sisters, and educate our own communities about our own complicitness in propagating racism in this country and in society at large.

Read More

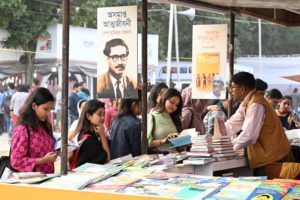

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More