After 50 Years of Independence, Is Bangladesh Truly Free?

By Bushra Mollick

Amar shonar Bangla. My dear Bangladesh. This year marks 50 years of independence since the 1971 Liberation War. The small yet mighty nation has taken strides over the decades, with a thriving economy; notable textile industry; taller, well-nourished children; and solutions to house the homeless.

As the nation and Bangladeshi diaspora celebrate the achievements that have propelled the country forward, it is integral to ask: are Bangladeshis truly free?

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the inequities marginalized communities face worldwide. In Bangladesh, lockdowns, limited access to COVID-19 testing, and a lack of resources for students exacerbated the wealth gap between the poor and the poorer. As Bangladeshis grew frustrated with the government’s mishandling of the public health emergency, many expressed their views online.

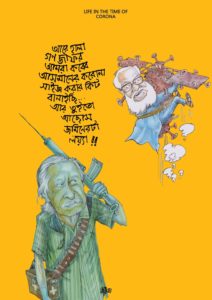

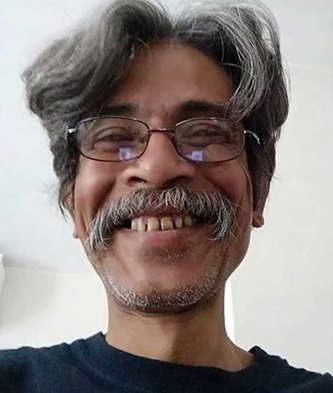

Ahmed Kabir Kishore took to Facebook with a cartoon journal titled, “Life in the Time of Corona.” Writer Mushtaq Ahmed posted his disappointments on Facebook, writing, “When a society laments the loss of an economy more than the loss of human life, it doesn’t need a virus, it’s already sick.”

The Digital Security Act (DSA) was passed in 2018 with the intention of creating a secure online environment. As more Bangladeshis gain access to the internet everyday, the government seemed keen on holding on to what could or could not be published.

Section 25 of the DSA allows for a sentence of up to three years for “intentionally or knowingly transmit[ing], publish[ing], or propagat[ing] any data-information [known] to be offensive, false, or threatening in order to annoy, insult, humiliate, or malign a person.” The legislation does not clarify what language would be considered annoying or humiliating, although it seems entirely subjective.

Section 28 deters the “publish[ing] or broadcast[ing] or causes to publish or broadcast anything…which hurts religious sentiment or values.” It prevents users from questioning and criticizing religious thought or ideas and can be punishable for up to five years.

The broad set of laws does little to define what can or cannot be posted and instead gives the government a wider net to charge and arrest Bangladeshis who allegedly “violate” the act.

The Digital Security Act was created not to protect Bangladeshis, but to protect the increasingly authoritarian government. It limits free speech and free expression and censors Bangladeshis.

Mushtaq Ahmed was denied bail six times. The writer died in prison earlier this year, after being detained for more than 10 months. After nationwide protests, and increasing backlash from international human rights organizations, Kishore was granted bail.

But only after his peer had died.

While the cases of Ahmed and Kishore garnered international attention, they were not the first or only instances of the DSA censoring and detaining Bangladeshis. Jagannath University student Tithy Sarker was charged with blasphemy for hurting religious sentiments in late 2020. Fifteen-year-old Mohammed Emon was arrested in Bhaluka over a Facebook post targeting Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s deceased husband. Journalist Shafiqul Islam Kajol was arrested in March 2020 for violating the DSA. Kajol was forcibly detained along with other journalists.

The Asian Human Rights Commission reports that more than 138 Bangladeshis were arrested in 2020 for violating the Digital Security Act. How many more will face “enforced disappearances” in the coming years?

Read More

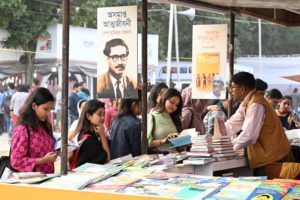

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More