Bengali Harlem

Bengali Harlem

BY ZARA KABIR

For many Bengali Americans, our roots began with our parents’ generation immigrating to the United States in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Some arrived as early as in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. This was only made possible by the “Immigration and Nationality Act” of 1965, which eliminated the national quota system that had effectively banned immigration from Asia for almost 50 years.

Lost in time, however, are the stories of Bengali Muslim men who passed through Ellis Island in the summers of 1897 and onward, bags full of chikan embroidered silks and other handicrafts from what was still British India. Colonial rule and the import of British-made textiles had all but obliterated the market for Indian goods within the subcontinent. Merchants were then forced to look elsewhere to sell their goods; thus, many Bengalis from Calcutta and elsewhere found themselves on the shores of New York City in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Published author and Film Director, Vivek Bald, lays out these long forgotten historical stories of South Asian Americans in his book, Bengali Harlem. Published in 2013, it went on to win the “Theodore Saloutos Memorial Book Award” from the “Immigration and Ethnic History Society.” Through the expert use of archival documents, such as ship manifests, Census records and newspaper clippings, Bald weaves an intricate narrative as he follows various Bengali men who functioned as part of a larger network of peddlers as they navigated changing policies, borders and racist immigration officials in the 20th century America.

Not only do the stories of such men defy expectations of White America at the time; they also break the stereotypes that South Asians hold for themselves. The western world, including America, in the grips of Orientalism, was utterly fascinated by the exoticism of the East and ancient India. Bengali Muslims exploited such fantasies to their advantage, carving out a market for Indian goods that helped create a flow of fabrics, cushions and throws from the Indian subcontinent to the boardwalks of New Jersey.

At the same time, Bengali men, who did not fit into the American racial binary, floated in between the worlds of Black and White America. Some even gained citizenship, if they were deemed “white” enough. Some, in the South, managed to ride in white-only spaces on buses, even after answering that they were from India. Others, who were darker-skinned, faced racial scrutiny and attacks.

Bengali Harlem, therefore, consisted of working-class migrants who brought much value to the cities and communities in which they resided. While immigration policies, at the time, sought to limit entry to “skilled” South Asians, the Bengali peddlers forced people to confront concepts of who was deemed worthy, who was not and why.

Bald does not only focus on the mercantile aspect of the lives of these Bengali peddlers, but also on their personal, including familial lives. As the title implies, many Bengali men settled in predominantly black neighborhoods, such as Harlem as well as New Orleans in the Jim Crow South. While many eventually returned to their villages, some men stayed, marrying Creole, Puerto Rican and African American women, thereby having interracial children, often with Muslim names. Eventually, these mixed families blended into their neighborhoods and were forgotten…until recently.

All of this is a far cry from the anti-blackness and

homogeneous exclusivity that, many times, defines Bengali-American communities

today. That is why Bald’s research and work is so revolutionary and a necessary

read for Bengalis from all walks of life. A documentary titled, “In Search of Bengali Harlem,” was released earlier this year, a

collaborative effort between Bald and Alaudin Ullah, whose father, Habib Ullah,

was one of the Bengali peddlers.

Read More

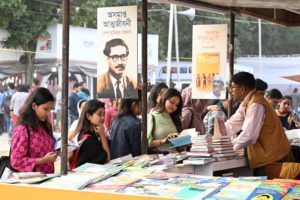

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More