Bengali Pride: A Look Into the Lives of Four Queer Bengalis

By Bushra Mollick

New York, NY

June 24, 2021

Pride Month is palpable in New York City as rainbow flags inundate sidewalks, hanging from apartment windows, small businesses, and outside religious institutions. The month-long celebration pays tribute to the 1969 Stonewall riots, a series of protests following a police raid at Stonewall Inn, a gay bar, in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village.

While the city commemorates Pride, queer Bengalis are often forced to remain closeted, hidden from the very movements founded to celebrate their identities. Homophobia, conservative views, religion, and archaic legislation limit the lives of queer people in Bangladesh. “Coming out” is not an option as homosexuality is illegal under Penal Code 1860, Section 377, which prohibits same-sex activities. Even if the code were annulled, hope for tolerance toward the LQBTQ community in the short-term remains grim.

The Queer Diaspora

As Bangladeshis migrated to the west, they carried their homophobia with them. Children of immigrants now find themselves forced to face familial pressures to remain chaste until adulthood, only to jump to an often arranged heterosexual marriage. Sex education and romantic partnerships are taboo topics in Bengali households. LGBTQ acceptance is not acceptable, let alone attainable.

Mina* Emir’s family emigrated to the United States in 2001. The Columbia University student majors in Ethnicity and Race Studies and identifies as queer and non-binary.

“I could never come out to my family,” she said, “In 2014, my mother took me and my family to the Islamic Convention of North America. At the end, little 12-year-old me went up to one [lecturer] and asked, ‘Is it okay to be gay? ’And I got my answer, which was, ‘You can’t control your thoughts, but you can control your actions. ’That pushed me into the closet for a long time.”

Like in most deshi families, queer Bengalis rarely feel support from loved ones. “Then I asked [my younger sister], ‘What would you do if I was gay? ’And she was like, ‘Well, it’s not my problem you’re going to hell.’”

Partho* is a PhD student based in Toronto, studying Political Economy of Religion in South Asia. He identifies as a gay male and advises the deshi diaspora to look past Article 377 as the ultimate reason for homophobia in Bangladesh.

“It’s the coping mechanism for a lot of us to think that our parents would have been more accepting if the British weren’t there and kind of externalize the blame, but I really urge young queers to [dismiss] external forces that may have produced that homophobia and instead start thinking about how to undo that from within the community,” he said. “I think that there’s a lot of richness in the queer history of South Asia that gets left under the rug. You have these beautiful texts that were published underground with heavily queer subtext that not a lot of people read.”

Partho urges the LGBTQ community to disregard community acceptance. “The Bengali diaspora here [in Toronto] is more of a working-class diaspora, so it’s much more tight-knit. I see a lot of young queers trying to seek acceptance from the aunties and uncles and just generally always kind of vying for that validation. I see that hindering them from accepting their queerness, because obviously when you try to look for that validation you probably won’t get it and it will be heartbreaking.

“I would say to other queer Bengalis, ‘Your validation should come from your friends and family who accept you, not from people who you know aren’t going to accept you.’”

Deshana is a teacher from Staten Island who identifies as a queer woman.

“I feel like [Bengalis of New York] readers need to know that being out and being proud is a really huge privilege,” they said, “There’s little Brown representation in these spaces. It’s because sometimes we can’t afford that. Our tuition, whatever it might be, might be swept out from under our feet, if our families find out about us.”

Deshana, whose family practices Buddhism and is originally from Kolkata, attributes heteronormative pressures to culture over religion. They recall a time when their father came to terms with acceptance. “I think it was the shooting in Florida and I remember my dad being really upset. He was like, ‘They didn’t do anything, these people are just existing. ’And then he said something that made me laugh. He was like, ‘I used to think that you shouldn’t be gay because gay people did it on purpose. But I looked it up on Wikipedia and I realized that you can’t control whether or not you’re gay.’”

The Florida news story refers to the Pulse nightclub mass shooting, during which gunman Omar Mateen killed 49 people and injured 53 more at the gay nightclub. It has been referred to as the deadliest attack on the LGBTQ community in American history.

Naurin Islam is a Long Island native and graphics consultant and Twitter manager for Bengalis of New York. The NYU graduate studied Global Affairs and identifies as a bisexual cisgender female.

“I never really used my bisexuality as, like, ‘Oh, this is me, ’as a ‘who I am. ’It’s just one part of me. As bisexual, we have something like biphobia: ‘Oh, you haven’t been with so-and-so, so you can’t be bi, or you’re in a relationship with a man, so you can’t be bi,” Islam said, “We don’t really talk about certain stigmas, as well as stigmas [around being bi] in the community.”

Islam offers a lending ear to queer and questioning Bengalis. “If you are afraid of coming out and you don’t have a friend, I’m actually always here to talk to as well,” she said, “Always seek out resources, especially South Asian queer groups that you can talk to, because facing something like this alone, having trouble coming out, or having trouble even just identifying who you are as a person, that can affect you mentally.”

[You can follow Naurin Islam on Instagram at @captain_nchaa]

No Fear in Queer: Support and Resources

According to a national survey by The Trevor Project, 48% of LGBTQ youth reported engaging in self-harm, 29% have experienced homelessness, and 46% report they wanted psychological or emotional counseling from a mental health professional but were unable to receive it.

While there are no confirmed numbers of the population of queer people in Bangladesh or queer Bengalis internationally, resources are available. As Pride expands globally and public opinion inches toward acceptance, queer Bengalis can also find support in unexpected places. “What empowered me to accept my queerness in the first place is my friends,” Emir said. “I found queer Bangladeshi Muslims on Twitter through our shared interest of the boy group, BTS.

We had a similar background, mirrored struggles, and the same love. They accepted me and I consider them my family, calling them my boro bon.”

Deshana, meanwhile, finds solace in sharing their pronouns with their students. “Where I work has a policy to give our pronouns. And when I did that, one of my students was so excited. She was like, ‘Oh my God. A they/them teacher. Finally, I’m so happy. I feel like I can use it now. ’I just need people to realize that representation is a lot more important than you might think. It’s not just political. It’s a real human thing.”

South Asian LGBTQ Support Groups

Apicha Community Health Center

Asian/Pacific Gays and Friends

The South Asian Sexual and Mental Health Alliance

South Asian Public Health Association

*Some names have been changed to protect individuals’ identities.

Read More

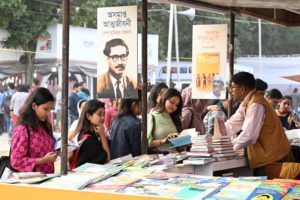

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More