Changing the Conversation: Mental Health and Sexual Assault in the Bengali Community

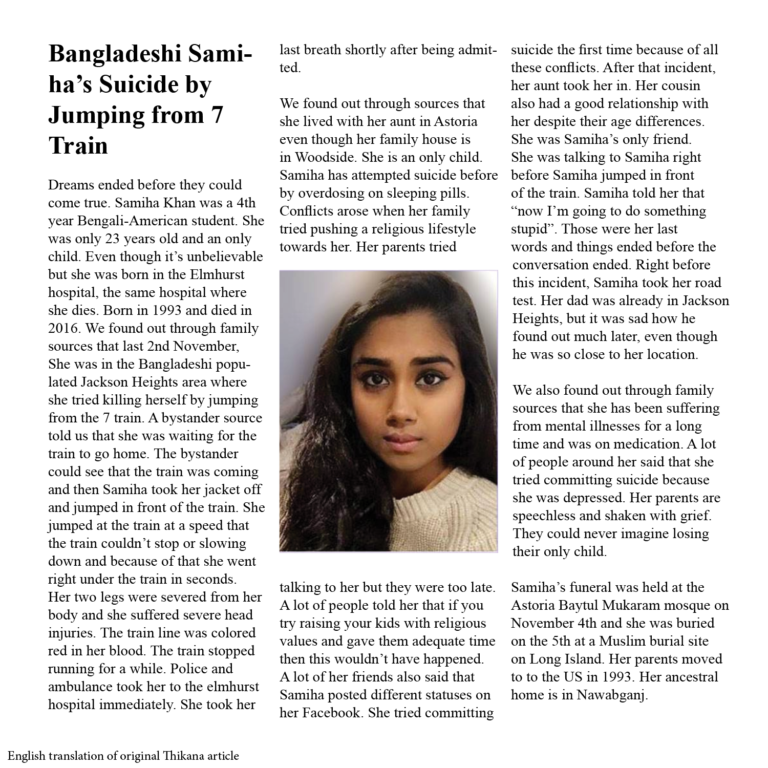

Suicide, Sexual Assault — Samiha Khan would’ve turned 26 this year. Unfortauntely, Samiha took her own life in November 2016 after 15 years of depression, anxiety, and sexual abuse from her own father.

6 days after, Donald Trump won the presidential election. At that moment, it felt like everything was against us as Bengalis. But in reality, we were pitting ourselves against each other within our own community when it came to mental health and sexual misconduct. Samiha’s death was a symptom of the toxic thought patterns in our community. We are let down and betrayed by certain people we trust who hold a level of power over us.

Bengalis have close knit communities, which inherently calls for leadership figures. Sometimes these figures hold power over other members of the community for religious knowledge, experience with US bureaucracy and immigration issues, and wealth. The community relies on these leaders so much that it becomes difficult to “out” them as predators since they are a key component of the functioning community that we’ve built.

We bring up these newspaper articles in light of the #MeToo movement in the South Asian community. These Bangla newspaper articles written by Bengali reporters in NY for their target audience: the older Bengali generation. They serve as hard evidence of the taboos about mental health and sexual misconduct among desis. The Thikana newspaper says “Conflicts arose when her family tried pushing a religious lifestyle towards her. Her parents tried talking to her but they were too late. A lot of people told her that if you try raising your kids with religious values and give them adequate time then this wouldn’t have happened.” The utter dismissal of her story and deference to her rebelliousness is a prime example of victim shaming.

We do not seek to discuss the details of her abuse and mental health, for that is her story to tell, not ours — even if the victim is deceased. Rather, let’s talk about how we as a community react to these situations; the way we frame these incidents; the capacity to which we are even aware of the deep-rooted problems that MeToo is on the tip of the iceberg for.

We cannot heal Samiha, nor can we bring her back. But we can change the way we treat and talk about mental health and sexual misconduct. We need to break the cycle and be better parents to our future children, better support systems for our kin, and all-around empathetic. We are products of the communities and households we grew up in — sexist, misogynistic, patriarchal, son-favoring, etc. It is time to unlearn and relearn.

Let’s start breaking the cycle by having conversations with our parents. Viewpoints can change after removing the language barrier and stigma around talking about certain issues, as we’ve seen with BLM.

We realize that talking about sexual misconduct is more difficult to talk about than most other issues at the dining table. Most of us grew up in households where we never have even uttered the word “sex.” But when presented with facts, even the most stubborn of people can start to listen.

And they should because of the staggering statistics that show just how common sexual misconduct is in the South Asian community. That alone should cue our family members to start thinking about “what if” this were to happen to someone I care about (mom, sister, wife, daughter, etc). That hypothetical situation itself should change the tone of the conversation. No one’s shirt length, religiousness, relationship status, class, education level, etc. can lower one’s chances of being a victim.

If parents are hard to get through to, let’s think of whether we would ever feel comfortable going to our brother or sister if anything were to happen to us. Because they are of our generation, perhaps they will understand more. And lastly, let’s change the larger community’s handling of these cases via the way they are framed and presented to the rest of us. Newspapers and media should not victim shame and should not make this an intergenerational problem of Western girls who do not listen to their Bengali parents.

This isn’t a Samiha problem. This isn’t a problem only when it affects someone you know. Her friend Farzana Rahman said it best “it isn’t an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’ issue. gender-based violence and mental health are issues that we are all responsible for. They are public health issues!”

Let’s listen. Let’s converse. Let’s change the dialogue in a thoughtful way.

Here are some of the dozens of links about her story:

- MEDIUM: Polarized: The Samiha Khan Story

- The Lily News IG Post

- THE ODYSSEY: How many Suicides Does It Take To Break The Silence

- THE LILY: The silent lives of childhood sexual abuse survivors in America’s South Asian diaspora

- WEAR YOUR VOICE MAG: South Asians – Our Silence about Mental Health is Killing Us

- WISE WOMAN: Samiha’s Legacy

- IRENE KHAN Facebook Post

- HAUTE HIJAB: Childhood Suicide Warning Signs and Seeking Help In Our Muslim Communities (Part Two)

- INDIA ABROAD: Maintaining an image worsens mental health issues among Indian-Americans

Read More

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More