Grief After the Passing of a Loved One

Grief After the Passing of a Loved One

By Tamara Syed

@tamarasyed

This article is part of a series called, “The Many Faces of Grief.” As someone who has experienced various forms of grief, I hope to help others navigate through this difficult, but necessary emotion.

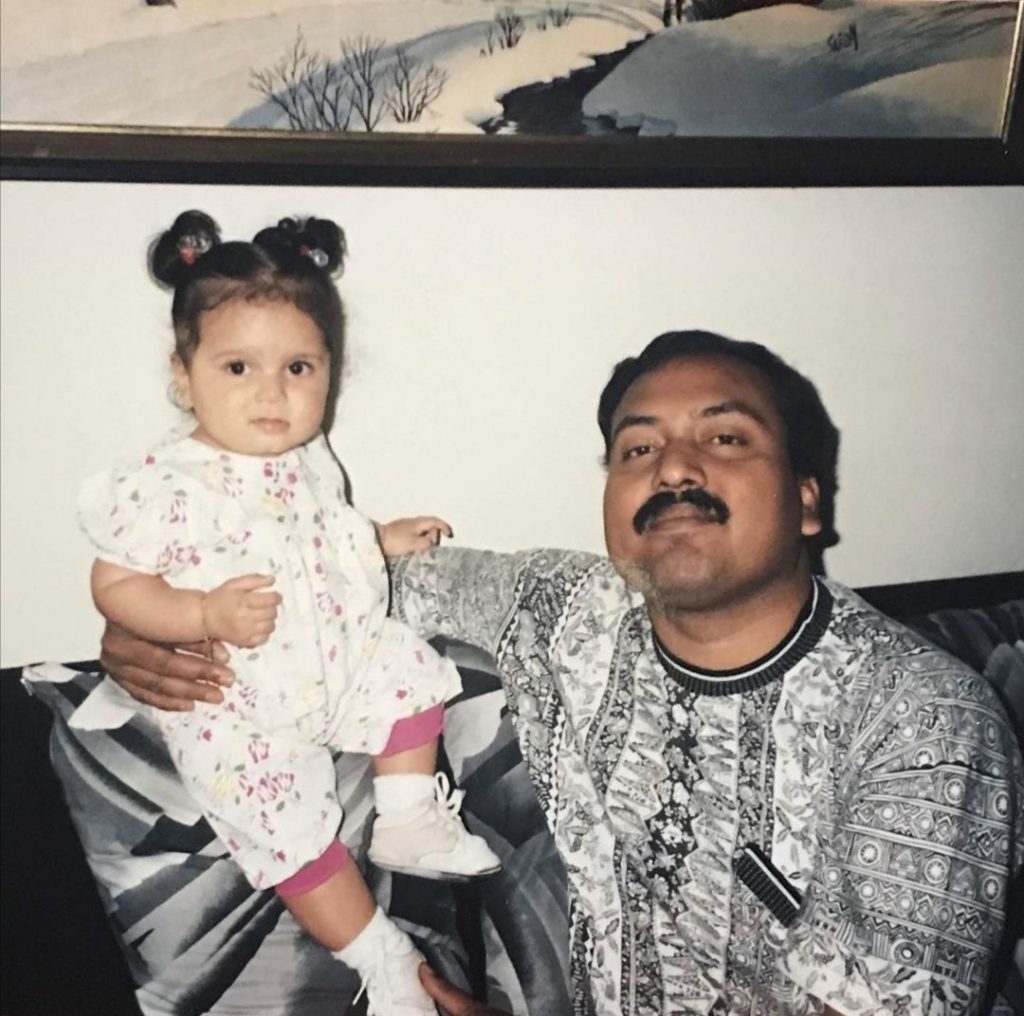

For me, in a way, my father had died twice.

The first time, I was 12-years-old and he left us after my parents had divorced. After that, he was in and out of our lives until I suffered a nervous breakdown at the age of 15, during which I called him, hysterically screaming, “Why did you leave?! Please, come back!”

He was living in Iowa at the time and hopped in his boss’s truck driving over 1700 miles across the country to our home in Los Angeles. I wonder what he thought about on that drive over, I wonder if he ever forgave himself for leaving. When he arrived, he couldn’t sit in the same room as my mother – she was giving him a hard time, rightfully so. He turned to me and said, “Do you want to go on a trip?” I packed up a bag and we drove off for a father-daughter weekend.

My father died in the summer of 2020. It wasn’t COVID. In fact, it came as a shock; he was 66-years-old and his health was improving. I hadn’t seen him since March: COVID restrictions, evictions and moving out of state kept us apart. A lot of people say they were “grateful for 2020” because of some frivolous reason like discovering they loved puzzles. Sometimes I say it too, because of the lessons it taught me. But, I would rather have my father back.

Losing a loved one is like reaching out your hand to something that isn’t there. Misplaced keys – wait, no, something more valuable, like a locket. Or a family heirloom? That’s not right. Losing someone is just that – indescribable. It feels empty, vast and endless. The keys you will find again, the locket you can replace and a family heirloom you could forget. A loved one, a person, your person – is not interchangeable; he/she can never be replaced. With this knowledge, you must learn to go on, living without them. Knowing that the time spent together was worth it, that it was enough.

One thing about losing a loved one is that things remain unsaid. I never fully shared the trauma I felt after my father left, with him. My father wasn’t equipped to lead that conversation and it fell onto my shoulders. If he were alive today, I would tell him, “When you left, I thought it was my fault. I’m sorry that I slammed the door in your face when I was 10.” I imagine he would reassure me by saying, “It wasn’t your fault.”

I blamed myself for glossing over the bad shit and for focusing on how our relationship looked at that moment. It ate away at me so much that I mostly ignored his calls those last few months before his passing, but I kept his voicemails. If your grandparents, siblings, or parents have left you voicemails – keep them. Download them onto your phone, today. I don’t know what happened to our family videos so this is all that I have left.

There was this voicemail where I hadn’t answered my father’s phone calls for three days and he asked, “Are you okay?” His voice echoed. It’s difficult sometimes, to talk to our parents, especially to tell them that they caused us so much pain, but the weight of things left unsaid is unbearable. Our parents probably never had these types of conversations, so tread lightly, but push through the discomfort anyway.

I’m not sure how to reconcile with the things that I did or how we spoke like I wasn’t holding a grudge against him. For example, I told him I was in Reno, “There are so many maskless people here.” He laughed and then, I probably said something snarky, which he would then laugh off again. A week before he died, I remember missing a call of his and when I called him back, he sounded different. I told him I had good news, the unemployment checks that took months to go through just cashed into my account. I was rich! He told me he was so happy to hear that. “Take care of yourself,” he said. Those were his last words to me; his energy was contagious and I put my phone down, smiling.

As a taxi driver, a personal chauffeur to political diplomats and even a music producer, my dad drove a lot throughout his life. Despite his exorbitant mileage, he somehow always found a way to take me to school. I remember he used to tell me, “I can’t wait till you have kids so that I can drive them to school.” Sometimes, I think that my dad is still on that long drive from Iowa, singing to himself, excited to come back home to spend time with his daughter.

Read More

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More