Growing up Bengali in the South

Growing up Bengali in the South

By Janan Sarwar

@rxjanan

I grew up in a rural city of America as a child of hard-working Bengali immigrants. In elementary school, we were required to learn country line dancing, the teachers were referred to as “Yes, Ma’am,” and “No, Sir,” and it was normal to get stuck on the road behind a tractor. Yes, Bengali communities existed in the South, let alone have been thriving and growing exponentially since the 1970s.

My childhood experience is like many others who found themselves living in a community very unlike them. When my dad finished his PhD program in Chicago and was seeking a job as a university professor, he looked all over the country. One of the first institutions to reach out to him was a small, public university in Tennessee, where the department consisted of professors with international backgrounds. My father mistakenly took that one diverse department to be representative of the entire South, which is an ironic reason for my Southern upbringing.

Nevertheless, I find our parents’ generation to exemplify three outstanding characteristics: resourceful, bold and hospitable. Using the phone book to look up names that sound Bengali was simply how to network in the 80’s. This is how, through word of mouth, one would hear about discount airline tickets to Dhaka or where to buy groceries that reminded them of desh, like shutki or achar… Many of the OG Bengalis who immigrated to Tennessee were there with advanced degrees, seeking university positions in the sciences, medical professions or sponsored by one of the aforementioned. These Bengalis held on to their culture, country and mother tongue, and all their kids came along for the ride.

There was a time in my youth where my family knew all the Bengali families in the local community. Our town was about 45 miles away from the city where most of the Bengalis lived. Despite the drive, like other Desi communities, we would gather on weekends at each other’s houses to eat royal meals on paper plates. Fathers discussed politics, interjecting in booming Bangla and English, aunties would talk about their children’s SAT scores or about who would not give away their secret mishti recipe. All the kids sat on the ground, glowing from the light of a box television set tuned to a late night show we probably shouldn’t have been watching or tangled in the Nintendo controllers of a “Donkey Kong” competition. As we grew older and our parents moved from apartments to homes, I recall gathering, but now segregated with the girls in our itchy frocks or salwar kamizes, giggling about our complicated lives. Later still, the Bengali association would rent out club houses or community centers for cultural programming. By 2022, Bengalis have become integral members of the community in many small towns. The innumerable organizations and multiple generations of Bengalis in Tennessee and the surrounding Southern states, make it impossible to keep track of everyone.

However, like many others who struggled with owning both our cultural and American identities, I often reflect and empathize with those who had two lives growing up. On weekdays, in Americanized clothing, it was difficult to see myself represented in any storybook at the library. In 2002, I remember clinging on to a story called, Born Confused. As a middle schooler, this was the first of its kind with a Desi female main character in a young adult novel. Despite having a strong interest in writing and creative arts, I followed the dutiful and stereotypical path of studying a medical field and pursued medical publishing. Fast forward to the present, thankfully, I recall how resourceful and bold my parents were. I am now a mother and wife, raising three young Bengali/Pakistani/American daughters ranging in ages 2 to 6-years-old. We live in a multicultural society, where culture is embraced and being global citizens is an asset. And believe it or not, I have found myself back again living in the South!

My experiences have opened up doors to the art and science of storytelling and I am now able to use my voice to unapologetically highlight, elevate and embrace my culture. Now, it’s my turn to share hospitality and invite my Yemeni and American neighbor over for cha and channachur so our children can play together and talk to each other about their unique and beautiful backgrounds. Admittedly, I sometimes use paper plates, attempt to recreate Bengali recipes (thanks to calls to my mom and Chili Pepper Cooks) and fondly wear my mom’s vintage saris and churees.

Above all, I find delight and hope in the next generation. My children receive a foundation rooted in perseverance, hospitality and food, yet also, the limitless potential to grow into whoever they want to be.

Read More

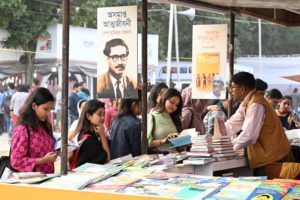

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More