Misha Chowdhury’s “Public Obscenities”: Off-Broadway Bengali Playwright Addresses the Beauty of Art, Connecting Culture and Queerness

Misha Chowdhury’s “Public Obscenities”: Off-Broadway Bengali Playwright Addresses the Beauty of Art, Connecting Culture and Queerness

BY

SHAOLIN BARID

Graphics: All shared by Blake Zidell PR representative. Production photos taken by Julieta Cervantes

The brilliance of South Asian culture meets the stage in Misha Chowdhury’s off-Broadway directing and playwriting debut “Public Obscenities”. Co-produced by Soho Rep and The National Asian American Theatre Company (NAATC), “Public Obscenities” is an incredible testament to Chowdhury’s inquisitive approach to the creation of art from the act of art-making itself while also tackling on the subjects of queerness, culture, and language. Misha Chowdhury speaks on his perspective to his culture and the way he finds his art entwined with his experience as a writer and director.

Tell me about your background. How did you get into theater, writing and directing plays?

I was born in India and my family is still mostly in Kolkata. I moved here when I was very young but I spent a lot of time back and forth between my family home in Kolkata and I grew up in Massachusetts. My parents are physicists but my mom is a singer and my dad is an amateur theater person. He did a bunch of plays and he actually has a little Facetime cameo in the show so I think my early relationship to performance and to theater came through the long tradition of poetry and music and theater that is so interwoven into my life. So when I go back to my family’s home … we lived in this sort of joint extended family home, they would gather the whole family for these concerts and we would sing and my grandmother was present. That sort of hearth and gathering place was my sense of coming together and doing things collaboratively around in a circle together.

It was what I longed for the most growing up and it was very absent to me in the states. I grew up in this little town called Wayland MA and there were like two other Indian kids in my high school class and I didn’t have an Indian community in the town that I grew up in. I found my way into the theater through this amazing high school theater program that was like an ensemble community driven theater in terms of this kind of rigorous process of leaving your ego at the door and making something that is greater than you with a group of people that you might not otherwise be in conversation with. And many of the people that I went through that program with are still theater makers here in the city so I really credit that program and this one man Harley-Davidson riding guy from Rochester NY with opening the doors to theater for me. When I was in college I was invited into a community of queer women of color and my mentor in undergrad was a queer chicana American and she would always encourage me to to write in my own language but I was always terrified of doing that because I was like ‘How would I ever cast such a play? Who would come to see it?’ If I wrote the way that I actually experienced the world it would have to be fully in Bangla and fully in English not in some sort of entirely hybrid Banglish. I graduated from college 16 years ago now and this [play] is the fruition of that call to action from my mentor in college in some ways, now that I have the resources and the support that I need to really do a bilingual play the way that I want to be able to.

What was your experience like directing Public Obscenities specifically?

I mean we’re in the thick of it right now. It’s been this amazing process of being proven wrong. I’ve been reading this play for two years now and we did an early audio version of it last summer and I was really apprehensive that we wouldn’t be able to cast the play given how specific the requirements are around fluency and gender. The main character is someone who speaks fluent bangla but they grew up in the States and speak English with an American accent like us. Who are professional actors from our community who can take four months to be here in the city and do this work? It was an amazing year and a half long casting process with TBD casting who works with Soho Rep a lot. I’ve been working as a professional theater maker for a long time now. I had forgotten how much I like being in a rehearsal room – this room has been so joyous there’s so much like generosity and humility. Everyone in the cast is having their off Broadway debut, people have been flown in from all over the country, half the cast is Bangladeshi, half the cast is like a West Bengali origin which is also so moving to me because I feel like our two communities are oftentimes kept apart. I think in our generation, in the diaspora there are more opportunities for like cross pollination between those worlds and the writing process is where my head has been for most of the last two years and then it’s such a quick and dirty rehearsal process in these off Broadway – it’s like an intensive like four weeks before we meet in the audience and we’re in the thick of that right now and every day I come into rehearsal and I can’t believe this is happening that I’m doing this. It’s a super intergenerational cast too – there’s a woman who is playing the grandmother character who only appears on video. To tell this story with the people who live and breathe the story so deeply is so fulfilling.

Can you talk more about how the play magnifies the importance of language and having both Bangla and English?

The play is about a Bangali American PhD student who goes back to Kolkata and the whole play takes place over the course of 10 days during his and his boyfriend’s trip back to Kolkata. The material of the play is really about how we as the audience experience these subtle code switches and shifts in language. We are experiencing the play in many ways through Raheem’s meetings – [being] dropped into this chaotic family environment and people are translating for him. There are deliberate choices that we make around what is and isn’t subtitled in the play and there are scenes that are fully in Bangla, there are scenes that are fully in English and there are scenes that are a mixture of the two where there is a constant translation going on in real time.

I really wanted to make a piece of theater that was rooted in a deep naturalism around language. We only experience subtitles starting in the 4th scene of the play which is entirely in Bangla and then the play is about cinema and photography too so this experience of subtitling comes out of the vocabulary of cinema. I’ve been really inspired by films like Minari and The Farewell and other Asian American stories – not South Asian American stories yet – but I’ve seen films that really demonstrate how an American play or an American movie can be in a “UN foreign language”.

This play was inspired by your uncle handing you this dream that he’s had and telling you to make a movie out of it. My perspective on that and how you navigated that was that: it’s someone else’s dream and whoever has the privilege of having those dreams and then hearing those dreams can create any sort of art with it. Your art was Public Obscenities and I just want to clarify with you– did I get that right and was that your intention with making it?

I wanted to do something with this because I was like “I don’t really make movies I’m not going to make a movie out of this dream” but what was so moving to me about that experience was my uncle gifting me this dream and saying “Here you’re a director, you go make it” was that the play is less about the dream itself and more about that question of who gets to be an artist. My uncle didn’t necessarily think of himself as an artist even though the act of him sharing that dream with me is art making because he was so detailed in sharing the screenplay that he had in his brain with me.

Having a queer perspective on everything was very unique and there were moments that the main character described his sexuality, his virginity and really honest reactions and interactions to those types of topics. How did you navigate writing about topics like that considering they are touchy for some communities?

Part of the play just comes out of an autobiographical experience and the landscape and environment of the characters in which the play takes place is very true to my own life. I am very lucky in that my parents were the first people I came out to when I was a junior in high school in like 2001 and I’ve been out to my entire extended family. My partner and I have traveled to Kolkata three times at this point and oftentimes it feels as though stories about queerness in our communities have to be justified because the narrative at large is that queerness and Bangali-ness must be in conflict with one another.

There is obviously this truth of complicated conversations around body and sexuality and taboos around it in our community which are very much woven into the story that I’m telling in the play. I have had an enormously liberating experience being a queer person back in Bengal because when I would go back I was just surrounded by the heart of my family. There are these rich long lives of queer people in our community forever. My queerness was always about my relationship to my family and my parents and I think in many ways I’ve retained my fluency in the language and my interest in the culture because I was just tethered to this woman’s heart. I was always following my cousins, sisters, my aunts and my mother around and being interested and in many ways those women were the holders of the culture.

What were some of the challenges that you faced while writing this play?

I have been a writer for a very long time but this is the first time that I’ve written a solo-authored good old-fashioned play.

In some ways this wasn’t a challenge surprisingly but somehow it was such a trick for me to register to those voices that live as deeply inside of me as they do that I can write from their perspectives even though I don’t have that language. As a writer it reminds me of when I read Zadie Smith’s “White Teeth” way back when. I was like how is it that there were these amazing characters in that book and how did this West Indian woman from London–these characters from my community –feel so alive and so true.

As a black woman growing up in London, it was so woven into the fabric of her experience and it feels almost to me in my writing that this play [Public Obscenities] has been a process that you’re excavating fluencies that I didn’t know that I had. The challenge has just been overcoming my own doubts around the [possibility if an] off-Broadway theater can produce this play in a way that won’t compromise the authenticity of what I want to do. Some of the things the play is dealing with are things that folks in our community may never have heard uttered so explicitly publicly and I’m both excited for it and a little bit terrified about what that encounter with the audience is going to be like once we invite them.

What do you hope your audience takes away from Public Obscenities?

I love the reason that I make theater because I want to make things that can’t really be reduced to the thesis statement. My favorite work is work that I have a hard time putting a finger on precisely. This play has required me to be rigorously attentive to life and my hope is that people come and see the show and are invited into like the thickness of a world that they may be super familiar with or a world that is completely unfamiliar to them.

That universe is so vivid that they feel [they go] into that universe and I believe that kind of specificity results in something universal. The play deals with questions around desire for home, longing, body insecurity, intimacy, grieving and generations and I think those are things that I hope that everyone in the audience is able to see themselves reflected in some way shape or form. I’m mostly excited to hear what audiences take away from it and that will really teach me what the play is doing.

Read More

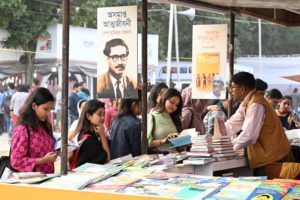

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More