The Impact of Mister Rogers and PBS on a Whole Ghusti of Bengalis in the ’90s

By Kamrul Khan

On May 1, 1969, Fred Rogers appeared before the U.S. Senate commerce committee requesting funds to help support the growth of a new concept – national public television.

Nearly two decades later, I got off a plane from Dhaka to New York and saw snowflakes for the first time. I remember the plane ride vividly: the turbulence, the undercooked and unseasoned food, the movie that was playing. It was Pee Wee Herman’s Big Adventure. Yes, watching Pee Wee Herman was the last hurdle I had to cross to have access to a better life in the United States. I knew almost no English and I still remember the first day of school (3rd grade) when my teacher asked me to spell my name. I knew what my name was, I didn’t know what spelling it meant. So I kept repeating my ‘dak nam’ (family name) and all of my family members’ names. Looking back, the teacher could have easily explained what spelling meant, perhaps by saying, “My name is Mr. Smith, spelled S-M-I-T-H”. Instead, he allowed the class to laugh at me. Ironically, by the end of the year, I was one of his favorites. Mr. Smith would constantly use me as an example and say, “Look at Kamrul, he just came to this country and look at him.” But what was it that had helped me excel in a language that I barely knew in such a short timespan?

I learned English from watching Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, Lamb Chops, Reading Rainbow, and later on Sesame Street on the Public Broadcasting Station (PBS). The quiet, genuine, and stern yet relaxed manner in which Mister Rogers spoke to me through the TV screen was juxtaposed with the loud, crime-infested, odious neighborhood outside of my apartment in East New York in the 1990s. For that half hour, I could forget about the chaos that occurred outside of my front door and sometimes in my school. Mister Rogers took me to the land of make-believe, where everyone spoke courteously to each other, the train ride was quick and efficient, and everyone was color blind. Mister Rogers, as I later found out, was literally color blind. The story goes that he hated what TV had to offer for kids at the time, which involved lots of pie throwing, and vowed to create a children’s program that was as wholesome as it was educational. This was also a time before tutoring centers. A majority of Asian households, specifically Bengali, that can afford to send their children to these centers, send their children. However, in the 1990s, these didn’t exist. So Mister Rogers filled the void. Teachers did not have the time, with a full class of miscreants, to give me individualized attention, so it was by watching “Learn to read” that I grasped how to read and spell. I did receive English as a Second Language (ESL) classes for the 3rd grade, but because of everything I learned from watching PBS, I was exempt from it a year later.

On that day on the Senate floor, Senator John Pastore, the senator from Rhode Island who led the hearing, had never seen nor heard of Mister Rogers’ television show. The senator also had a reputation of being a difficult negotiator and a tough shell to crack. It took Mister Rogers just six minutes to convince the gruff and impatient senator to pledge $20 million for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting which operates PBS. “I am supposed to be a tough man, but I just got goosebumps,” is what the senator responded to Mister Rogers’ testimony. Repeats of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood stopped airing on PBS stations in August 2008, years after the death of Fred Rogers (March 20, 1928 – February 27, 2003). In the era of influencers, cyber bullying, school shootings, and rampant mental health, we need voices like Mister Rogers to tell us in his compassionate tone, as he told those from marginalized groups, “God loves you just the way you are.” Also, while not every parent can afford to send their kids to tutoring centers, and can’t be sure of what their kids are consuming on the internet, it’s reassuring to know that Mister Rogers and the multitude of other PBS shows will be available to children to consume for generations to come.

Read More

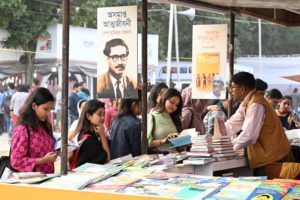

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More