My Long-distance Relationship with Bangla

By Shaolin Barid

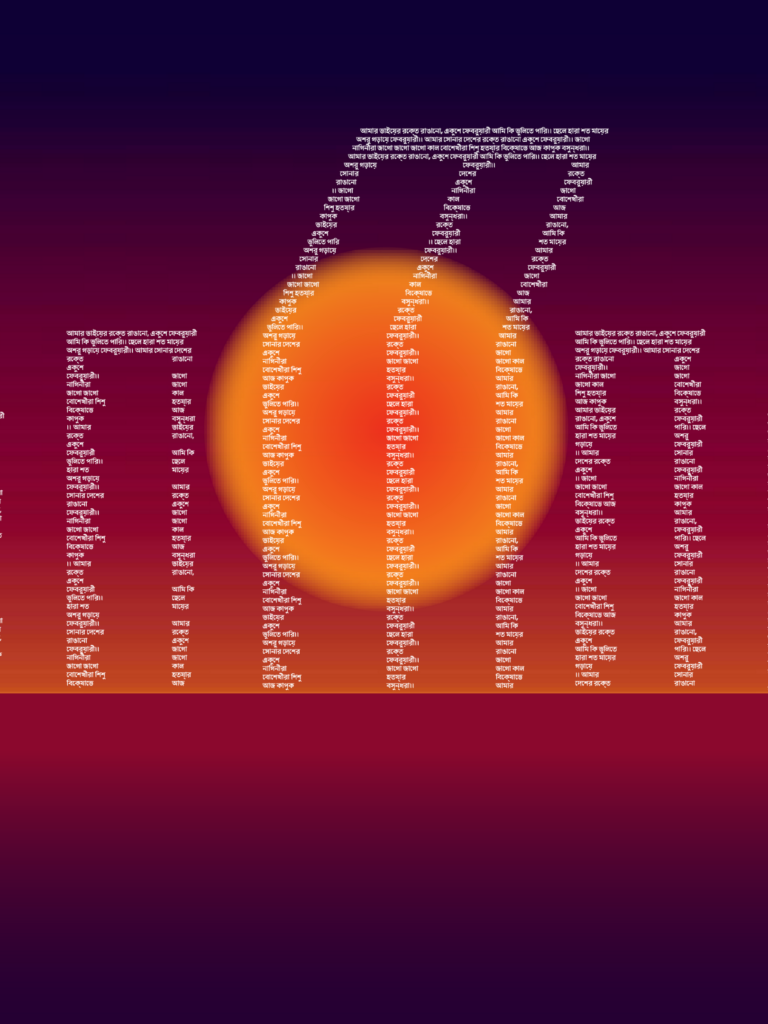

The historic events of February 21, 1952 mark an important day for the Bangla language and its preservation. On this day, college students from Dhaka University, Jagannath University, and Dhaka Medical College fought for Bangla to be the national language in what was then East Pakistan. The protests culminated in the Pakistani military using massive force, leading to the deaths of many young martyrs in the fight for linguistic freedom.

When I think about the struggles surrounding the preservation of Bangla, I evaluate my own relationship to the language and its cloudy presence in my life.

I have a complicated relationship with Bangla, something which many of my close friends and family may have noticed. I was born and raised in The Bronx and for my whole life, I have molded my comfort to the likes of English and Bronx slang. It wasn’t until recently when I realized how crippled my Bangla sounded to some relatives in Dhaka that I truly started evaluating the relationship I share with the language.

Why am I slowly evolving further and further away from my mother tongue?

It’s actually pretty simple. I never had to note the importance of speaking in Bangla because I was never obliged to speak it in America. I’ve subconsciously gravitated towards English-dominant spaces. It’s fair to say that it has become easier for me to attach more curiosity to understanding common English phrases rather than stay stagnant in my mixed Bengali and the American understanding of the world. Sometimes I see my mom confusedly look at me when I repeat some of those same phrases or American slang at home, but she never submits to any further interpretation.

And what about communicating with my parents and relatives?

My parents, in their more than two-decade-long stay in the city, have slowly assimilated to American culture in many subconscious ways. As they juggle work and take care of my siblings and me, they’ve gained an incredible understanding of how communication operates in their work settings and mixed Bronx-bred communities. It’s important for them to learn English to integrate into primarily English-speaking environments. However, my mom still talks to me in Bangla, in hopes that I don’t lose touch with my mother tongue. Of course, I respond in English, unsure as I am of my linguistic abilities in Bangla.

Speaking Bangla was never my strong suit. Still, I try my best. My bilingualism has never been a balanced duality and, at most, I can understand Bangla better than speak it. Oftentimes, I can sense my mother’s disappointment when I communicate with her in English.

She tells me that I’m forgetting how to speak to my own grandparents back in Bangladesh and adds, “বাসা ছাড়া বাংলায় কথা বলার ও চর্চা করার আর কোনো সুযোগ নেই l যে ভাষার জন্যে মানুষ প্রাণ দিয়েছে, সে ভাষাকে আমার সন্তানেরা ভুলে যাচ্ছে। আমার নিজের মেয়ের সাথে কথাবার্তা বলতে গিয়েও দেখা যাচ্ছে যে আস্তে আস্তে আমি নিজেই তার সাথে ইংরেজিতে কথা শুরু করে দিয়েছি। এক সময় ভাষার প্রান্জলতা হারিয়ে ও নিজের সময় বাঁচাতে আস্তে আস্তে ইংরেজিটাই আমাদের মধ্যে যোগাযোগের মূখ্য ভাষা হয়ে দাঁড়িয়েছে। এখন ভাবছি যে এ ব্যাপারটা অন্যভাবেও তো হতে পারতো। ভাগ্যবশত: আমাদের এ দু’ প্রজন্মের মধ্যেকার যোগাযোগ ভাষাগত কারণে বিচ্ছিন্ন হয়ে যায়নি, তবে দু’জনের মধ্যে বাংলায় যোগাযোগ আস্তে আস্তে ক্ষয় হতে চলেছে। আমেরিকায় জন্মগ্রহণকারী বাংলাদেশি বংশোদ্ভুত ছেলেমেয়েদের দরকার বাংলা ভাষা-বান্ধব পরিবেশ ও পরিস্হিতিতে বাংলা ভাষার নিয়মিত চর্চা ও প্রয়োগ করা। ইংরেজি প্রধাণ দেশ ও পরিবেশে থেকেও এখানে বাংলা ভাষা চর্চার প্রচুর সুযোগ সুবিধা রয়েছে যার মাধ্যমে এ ভাষাকে সুরক্ষা করা যায়।”

(“They’re forgetting the language people have died for. I ended up learning English and now communicate with my daughter in English in order to keep up with my own children. Thinking about it now, it should be the other way around. Luckily, our connection isn’t gone due to us finding ways of communicating with each other in Banglish, but the process of communicating with each other in Bangla is slowly fading away. American-born children should communicate in Bangla especially in Bengali-based environments. There are endless opportunities to preserve the language even in an English-dominant society.”)

I yearn to master fluency in Bangla and often express that by mimicking what I hear from my family and relatives. I even go so far as to speak in simple sentences with my parents in an attempt to make small talk and better my ability to speak Bangla. I understand that the weight of being a Bengali-American can often tip me over too much to the point of losing connection to my parents’ Bengali roots, and it does bother me. Language is the door to a culture and while the Bengali-American community in New York City tries its best to preserve our culture, the language is being dominated by what is expected from Bengali-American citizens.

Read More

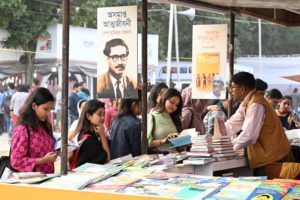

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More