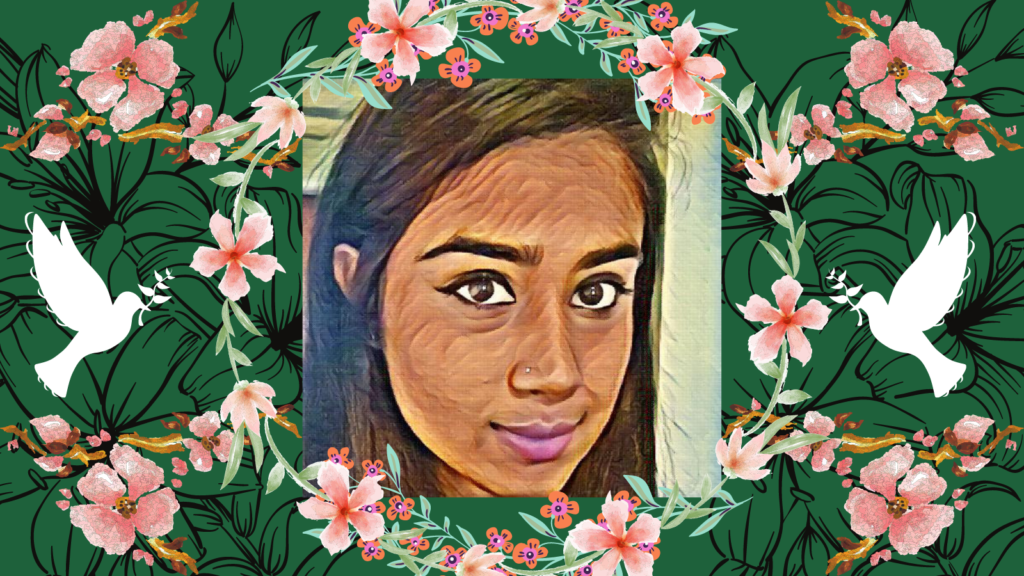

Samiha Khan, Five Years Later: How Can Our Community Support Victims of Sexual Abuse?

By Bushra Mollick

@bushramollick

Trigger Warning: Mention of sexual, mental, and emotional abuse.

This November marks five years since the passing of Samiha Khan. The 23-year-old jumped to her death on the 7 train platform of the 74th Street, Roosevelt Avenue subway station in Jackson Heights, Queens. Khan took her own life after suffering years of sexual abuse at the hands of her biological father.

Khan’s death highlighted a disparity within the Bangladeshi diaspora’s response. As younger generations of Bangladeshi immigrants, and children of immigrants, took to social media to share stories and spread awareness of her tragic death, older generations remained silent. The only Bangladeshi newspaper to highlight Khan’s death, Thikana, failed to mention the ongoing sexual abuse.

Khan’s passing, and the community negligence following her suicide, reflects a widespread, cultural issue; the taboo of sexual abuse and the dismissal of sexual abuse victims.

According to UNICEF Bangladesh, “Sexual abuse cases are hard to assess. Justice is inhibited by stigma and fear of risks.” There are no concrete statistics on the number of people sexually abused in Bangladesh and in Bangladeshi communities worldwide, as victims rarely report their abuse out of shame and lack of support.

“Shame isolates people,” said Dr. Rumana Mansur, a clinical psychologist based in Orange County, California. “Shame disconnects people and we tend to have a lot of shame in our upbringing. How would parents even go about talking about sexual abuse when they don’t even talk about the sexual part of it? There is the fear of social stigma and community values.”

Dr. Mansur highlights four key reasons for the silence surrounding sexual abuse victims and lack of justice:

- Family power dynamic: In Bangladeshi culture, it is common for parents to look at their children as property. If children are abused, it is up to the parents to decide if they will seek charges.

- Patriarchy: Bangladesh and the Bangladeshi diaspora, is a largely patriarchal society. Men are the head-of-household and women and children come after. Men are also, most often, the perpetrators of abuse.

- Economics: Often, the victim relies on the abuser for financial support. If the abuser is the father or breadwinner, victims will rarely speak out.

- Victim blaming: Cultural expectations place honor on the woman, therefore blaming her for the sexual abuse if her honor was “defamed.” Sexual abuse can affect anyone, regardless of gender identity.

Most victims of sexual abuse know their abuser as the perpetrator has access to the person through work, friendship or family.

Zain Mahmood is the co-founder and chief operating officer of Casata. He fell victim to sexual abuse while living in Bangladesh as a child: “I was probably four or five years old and we had chauffeurs to take us to school and bring us back. So, there’s a temporary chauffeur who came in, who was probably not vetted very well by the family. And he took me to school one day and he brought me back and he took me to his room and he molested me.”

“That stayed with me for a very, very long time. It was a deep secret that I’d never shared with anybody. I never went and told my parents or anybody, but I just felt something was wrong.”

Dr. Sarika Persaud is a psychologist at Fordham University at the Lincoln Center Campus and an adjunct professor for CUNY John Jay. She is known as Dr. Samosa on Instagram. “I’ve had a lot of clients who are South Asians and who have been through sexual abuse in their lives and by and large, it’s a very similar story,” she said. “They never told anyone because there’s this sense of, ‘If I tell my parents or I tell my family, I’m burdening them and I am responsible for my parents’ emotional health.’” Dr. Persaud also noted that many parents encourage their children to ignore the abuse.

“Maybe the parents confront[ed] the person, whoever it was, but it was kept very [under wraps], or maybe the parents spoke to the [abuser], but then still kept up the relations. So, they basically are giving mixed messages to their child,” she said.

It is uncommon for Bangladeshi parents to review sex education with their children. Their lack of knowledge and support for sexual abuse victims reflects their parents’ silence on the subject. The cycle of abuse continues as parents do not engage in these conversations.

Mahmood encourages victims of abuse to avoid self-sabotage. “It took me [years] of therapy. I had to learn how to unpack that incident and learn to stop blaming myself,” he said, “This is a very common thing for people who are sexually molested or taken advantage of, for them to blame themselves.”

“I talked to a Bangladeshi psychiatrist once many years ago. He told me this, he said, ‘Zain, you don’t know that in rural Bangladesh, there is a topic that men talk about very commonly. There’s a phrase, Amar bhaganer phol ami khabo na, thaar age ke khabe?’” This translates to, “Should I not eat the fruit of my farm before others?” This means a father should have sexual access to his own kin before another man does.

Samiha Khan fell victim to this very phrase.

Sexual Abuse: Signs and Support

“There are many signs that suggest a child may have been abused. “Some children are always daydreaming. People think they’re always daydreaming, but really, they’re kind of dissociating from reality,” said Dr. Persaud. “Children who are avoiding certain adults. They might not tell you why, but they become very anxious. Or some kids have a somatic reaction, meaning they have a stomach ache or some headache or pain, but they can’t say ‘I’m anxious.’ They’re like, ‘I have a tummy ache’ whenever they have to go see a certain adult.”

“If you notice any consistent or significant change in your child’s behavior, there’s no harm in taking them to a psychologist because some of the signs of sexual trauma can also be signs of something else.”

Mahmood insists on the importance of discussing healthy sex practices in order to better understand and deter sexual abuse. “In our culture, there’s so much stigma about talking about sexuality, about sex being a healthy enjoyment,” he said. “There’s nothing unhealthy about talking about sex, thinking about sex is a very healthy part of your life. If you can start that conversation, that automatically will start the conversation about what is not healthy, what is not right, what is not true. And there are some basic boundaries.”

Active communication is one factor in ending the abuse. Victims of abuse may not find support from parents or family, but may be able to find support from teachers or school counselors.

In order to deter sexual abuse incidents, it is integral to limit access to vulnerable children. “It’s not someone off the street. It’s not even someone outside of the family. It’s a lot of times someone in the family or close to the family,” Dr. Persaud said, “So what kind of rights are we giving these men who may or may not be a part of our family to have such unrestricted access to children? And why?”

Sex education can help end the stigma sexual abuse victims face. Experts agree that normalizing conversations surrounding sex can help segue into better understanding of sexual abuse. “There is a correlation of sex education and the sex abuse rate,” said Dr. Mansur, “We want more education and awareness. We need to create an environment of education. Educate parents, educate teachers, educate law enforcement. Let’s start there.”

Resources: A Note from the Writer

If you, or someone you know, has been a victim of sexual abuse, know that this is not your fault. Please share the list of resources below and remember you are not alone.

RAINN: Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network

Read More

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More