The Forgotten Nawabs of Dhaka

The Forgotten Nawabs of Dhaka

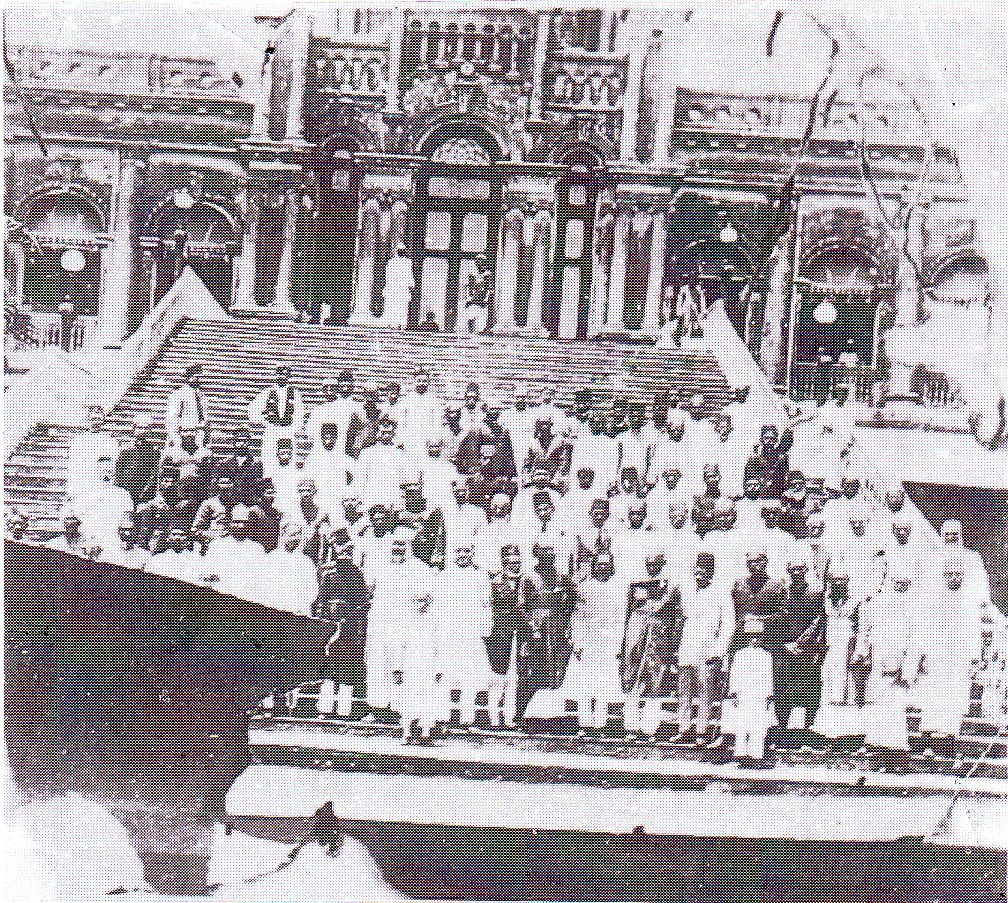

Credit:

Official photographer of the Dhaka Nawab Family, Public domain, via Wikimedia

Commons

Often regarded as Bengali royalty, the Nawabs of Dhaka were neither from Dhaka nor did they speak Bengali fluently. Much of their legitimacy and power rested in the hands of the British Raj, with much of the family’s legacy decimated by the time the British left the subcontinent in 1947.

The Nawabs’ lineage can be traced back to Kashmiri merchants who migrated to East Bengal during the Mughal era. These merchants, the Khwajas, spoke Persian and Urdu predominantly. They would ultimately settle in various localities in and around Dhaka, including Sylhet in the early 16th century. Quite successful in their business endeavors, the family patriarchs would eventually begin to invest in land auctions.

Khwaja Alimullah would be the first to assume the title of “Nawab” in 1843, as head of the family and estate. Nawab had been, historically, a title bestowed on Muslim rulers in the Bengal region prior to 1757, when the East India Company established British rule in India.

Perhaps, Alimullah sought to bring back the glory of such rulers. There was no questioning the Khwajas, who had since amassed considerable influence in Dhaka, had come to manage one of the largest zamindaris, in the province.

Despite this, the Nawabs still remained mostly Urdu speaking. With time, though, the dialect spoken by the Nawabs became known as Dhakaiya Urdu. As noted by P. K. Bandyopadhyay, “Urdu [was] the mother tongue of the Ashraf (the elite class) and Bengali [was] the mother tongue of the Athraf (the commoners).”

Alimullah would pass away in 1854, with Khwaja Abdul Ghani rendered as the head of the family estate. A fierce ally of the British Raj, it was Ghani’s loyalty in the years that helped establish his family’s legacy in Bengali history.

During the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, Ghani not only offered his support to the British, but he aslo provided counterintelligence. He is quoted to have said, “My presence in the station at this critical moment inspires my countrymen with hope and confidence in the British Government and prevents the evil-doers from carrying out their wicked designs.”

Ghani continued this pattern of colonial collaboration, forging close ties with British Lords Northbrook and Dufferin. In 1867, he became a member of the Viceroy’s Council. Less than 10 years later, Queen Victoria rewarded his allegiance to the Crown with the conferment of the title “Nawab,” making it hereditary.

Despite such close ties to the Raj, Ghani contributed much to the modernization of Old Dhaka as well. With the endorsement of the colonial rulers, Ghani introduced the panchayat mahallah, or local district, system to Dhaka. He also personally financed the building of the Buckland Bund, a dam along the Buriganga, as well as a water supply plant. Filtered water from the plant was supplied free of charge to the residents of Dhaka.

Furthermore, he established Victoria Park, known as Bahadur Shah Park today. He also helped restore and rebuild the garden houses of Dilkusha and Shahbag. Ghani was also one of the proprietors of the Weekly Dhaka News, introducing the first English newspaper in Dhaka.

Ghani’s son, Nawab Ahsanullah, donated generously to the development of Dhaka. He is credited with establishing an engineering college, a precursor to the national Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, or BUET. In 1901, electricity was supplied to parts of Dhaka for the first time, and it is said that Ahsanullah donated 400,000 rupees to the cause. From mosques to schools, there were very public institutions at the time that did not bear the patronage of Ahsanullah.

In the area of arts and literature, the Nawabs were great sponsors, supporting poets and writers of Urdu and Persian literature. Nawab Ansanullah himself wrote poetry in Urdu under the pen name of Shaheen. A book of his selected poems, Kulliyat-e-Shaheen, is preserved in Dhaka University today. It was also through the Nawabs that the first female actors performed on stage in Dhaka.

Despite their many contributions, Dhaka would soon forget the Nawabs. As unrest swept through East Bengal and anger at the British grew, the loyalty of Nawabs to Raj soon went out of vogue. By the time the subcontinent was partitioned, the Nawabs were quickly relegated to the past.

Even today, the Nawabs are often remembered for their vanity and colonial aspirations. Though their role in the colonization of Bangladesh cannot be denied, nor should it be forgotten, the reality remains that the Nawabs were one of the main drivers of cultural, social and economic development in Old Dhaka.

Perhaps, the best lesson we can learn from the legacy of the Nawabs, is of the brevity of their wealth and power. The story of the Nawabs only reminds us that our high stature in society today is ultimately temporary and our fall from grace is guaranteed. It is simply a question of when and where, so live in…really take in every moment.

Sources:

C E Buckland, Bengal under the lieutenant-governors., Calcutta : S.K. Lahiri, 1901

Taifoor, Syed Muhammed. Glimpses of Old Dhaka: a Short Historical Narration of East Bengal And Aassam [sic] With Special Treatment of Dhaka. Rev. and enl. 2d ed. Dacca: S.M. Perwez, 1965.

Khatun, Hafiza . Dhakaiyas and Gentrification in Old Dhaka. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. p. 4.

“Dhaka Nawab Estate.” Banglapedia, 18 June 2021, https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Dhaka_Nawab_Estate.

“Ghani, Nawab Khwaja Abdul.” Banglapedia, 18 June 2021, https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Ghani,_Nawab_Khwaja_Abdul.

Khan, Muhammad Mojlum. The Muslim Heritage of Bengal: The Lives, Thoughts and Achievements of Great Muslim Scholars, Writers and Reformers of Bangladesh and West Bengal. Kube Publishing Limited, 2013.

Read More

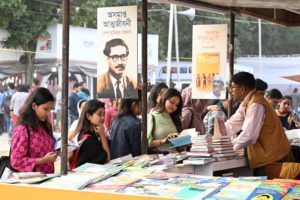

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More