The Unanticipated Gifts of Making Art

Bangladeshi American fiber artist Fatema Haque shares the unanticipated gifts of making art.

By Fatema Haque

- Each week, I spend 20-30 hours hand-embroidering portraits. I work almost exclusively at night, sitting in the ergonomic office chair at my desk. The area around me is lit by the warm glow of a desk lamp. I listen to podcasts, TV shows, and occasionally talk on the phone with friends. What remains constant is my 9:30 standing call: I FaceTime abba to talk through his insulin injection. What used to be a 30-second phone call has become a 15-20-minute FaceTime that strains my patience. He was diagnosed with Lewy Body Dementia a couple of years ago. He doesn’t always remember the time and sometimes forgets where he is or where to find the insulin. At other times, he doesn’t want to get out of bed and I have to coax him into turning on the bedroom light, leaving his cocoon, and venturing into the kitchen. I breathe, head bent over my embroidery hoop, pushing and pulling the needle through two layers of fabric, finding the calm within to give clear instructions: “The needles are in your desk drawer, inside the purple and white box that has 5mm and 32g written on it. Turn the bottom ring of the insulin pen till you reach 30 units. Yes, 30. Clean an area of your stomach with the alcohol wipe. Put the cap back on the pen and return it to the fridge.”

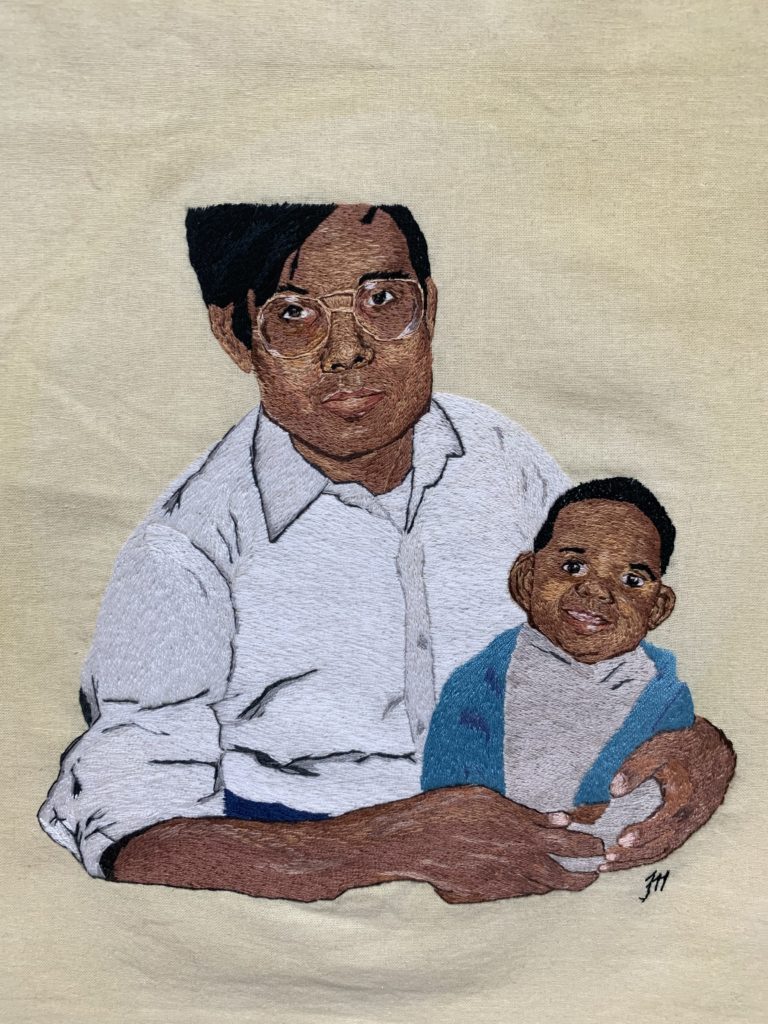

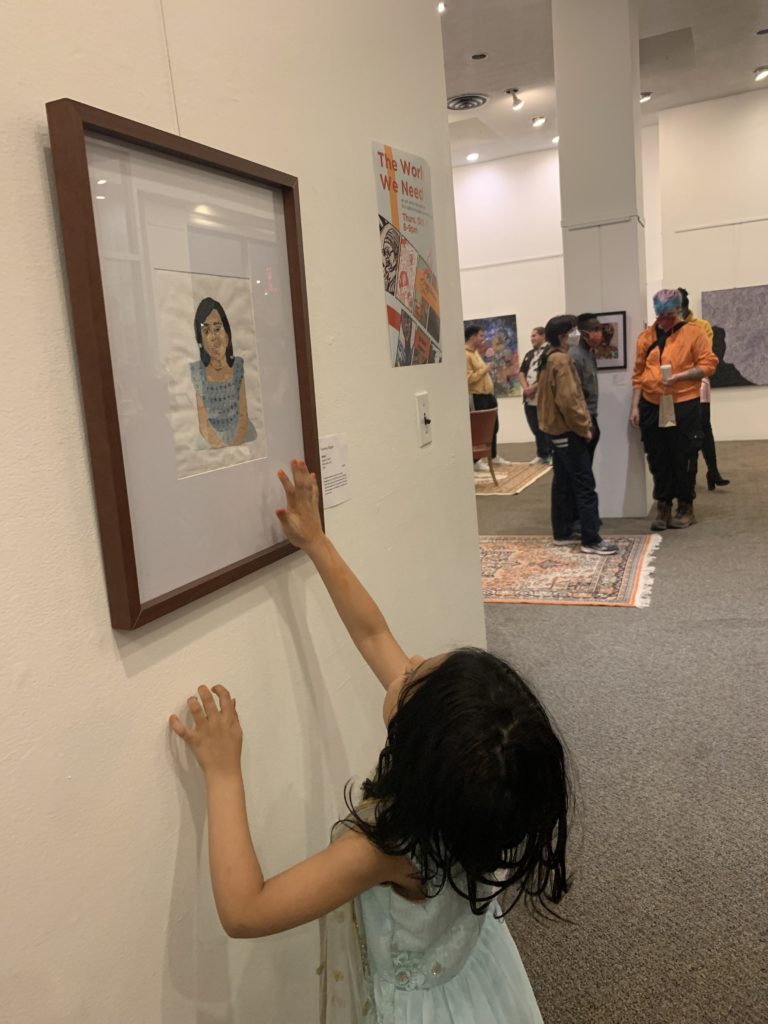

- On a Saturday morning at abba’s home, I sit at the kitchen table, embroidering the arms of a dad holding his infant daughter. My 6-year-old niece sleepily walks into the kitchen. It’s still early, and for hours, I’ve been the only one up. “His arms look like my dad’s,” she says. “Oh yeah?” I ask. “Yeah, and he wears glasses like my dad does. And he has black hair.” She goes on to list a few more similarities she sees between the portrait I’m embroidering and her dad, and I sit back in awe, listening to her see her world reflected in art. I still feel resentful that I didn’t have such reflections growing up, that the connections I found were tenuous at best. Reading Chinua Achebe’s “Marriage is a Private Affair” and telling everyone that Bangladeshis also participated in arranged marriages; seeing the name “Fatima” in the CD booklet accompanying Backstreet Boys’ Millennium and wondering if that Fatima hailed from Bangladesh; feeling excited over random TV shows name dropping Bangladesh when they needed an exotic or impoverished locale to reference. Never anything that was specifically made for someone like me with my dual identities of Bangladeshi and American. My niece won’t have that problem; her portrait has already been featured in a gallery and she got to see herself celebrated as the subject of art months ago.

- To source photographs for my exhibit Bangladeshis in Michigan, I post old photos of abba on Instagram and Facebook. There he is: in the leather parts factory where he worked for nearly a decade; sitting at a picnic table with coworkers, holding a can of Pepsi; standing in front of his rental home in Detroit wearing the navy blue winter coat that’s still in the back of his closet because he hates to throw things away. A woman messages me on Facebook, asking if I know the name of the man holding a can of WD-40; he is standing next to another man holding two freshly caught fish. That’s my father, I tell her. She asks if she can call me, talk to me about him. We are on the phone within minutes and then she tells me stories about abba from a period of his life I know little about: those years when he was in America by himself, without us. My father was good friends with her dad. He would visit them every Sunday, stopping by the only Bengali grocery store in town to pick up a few pieces of candy for her, and have breakfast with her family. She tells me that he was kind to her family, offering her father advice and comfort during difficult times. He told her about me, promising that one day when I move to America, she and I could have a playdate. After our conversation, I sit in tears holding the unexpected gift, a fresh story about abba who can no longer tell a coherent story of his own.

- On a late Saturday afternoon at abba’s, my ten-year-old nephew returns home upset. “You’re back so soon. Everything okay?” I ask. He had gone out to play soccer with the Bangladeshi boys down the street. He tells me that they kept calling him “white boy” even though he told them his name, which is clearly Bangladeshi. I want to rush out of the house and strangle the ignorant children who taunted him. “You are Bangladeshi and you are white,” I say. “Sometimes people will only see one part of us, but that doesn’t mean the other parts are any less real. I’m sorry those kids couldn’t see it.” He shrugs, masking his hurt and turning his attention to instructing his little sister as they tag-team a Minecraft challenge. Later, as I work on his portrait, I think about all the narrow definitions of Bangladeshi I’ve experienced. You’re not Bangladeshi enough if you don’t speak the language, read or write it, know your country’s history, wear the clothes, or celebrate the holidays. I think about how I’d forgotten the few times as a child I observed Pohela Boishakh and Ekushay February; how I wore the wrong colors to the celebrations as an adult while my expat colleagues dressed appropriately. To feel like an outsider among literal outsiders in your own country is a uniquely humiliating experience. I’ve spent a lifetime feeling both too Bangladeshi and not Bangladeshi enough, trying to make up for it by learning to cook everything from biryani to shutki, perfectly draping saris, learning the language and history and staying somewhat up to date on the politics. My nephew learned to make rotis when he was five years old, his circles admittedly better than my own. I wonder if he’ll use that to justify his Bangladeshi-ness; I hope he never has to.

- To embroider portraits of individuals is to spend time with them: the memories you have with them, who they were and who they are now, how you feel about them, how they might feel about themselves. I delay embroidering a portrait of khala, my maternal aunt, for six months, even though I had the reference photo picked out months in advance. In the photograph, she is wearing a royal blue sari paired with a hot pink blouse that matches the gold and pink borders of the sari. Her stare is direct, her lips black cherry. She wears plenty of jewelry: two necklaces, churis on one wrist, a watch on the other, gold rings on multiple fingers. My first thought looking at this photo of her is that she looks like a bad bitch, someone you shouldn’t fuck with. I respect the woman in this photo. I also worry about using it. She is fat, her face round and full, double chin visible. I recall ignorantly calling her botli, fatty, instead of khala, all through childhood, encouraged by other family members. Did I hurt her feelings back then? Does she hate looking at this photo of herself the way I’ve hated seeing photos of myself, when internalized fatphobia wreaked havoc on my psyche? I imagine people thinking I’m fat, snidely commenting that I must not eat very much, even if they’ve never said it directly to me the way everyone told khala. My privilege is that I’m American and I have an income; no one would say such disrespectful things to someone they might need assistance from. Khala never had that privilege; she had to bite her tongue and bear the taunting remarks, eating only one meal a day to shrink her body into something less mockable.

- The topic of Alzheimer’s and dementia follows me everywhere now that abba has the illness. While I embroider, I put on mindless TV procedurals and soap operas that don’t require my eyes to follow the story. ABC has a General Hospital streaming channel on their website, a show that I obsessed over as a teenager. As luck would have it, the channel is airing episodes from 2018 when Mike, Sonny Corinthos’ father, is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. I remember when I first started watching General Hospital, Mike had a gambling problem that Sonny hated and a secret daughter that Sonny eventually came to accept. Now, Mike was living with Sonny and Sonny was devotedly recreating the better moments of their relationship, inviting Mike’s friends–the residents of Port Charles–to celebrate Mike’s life. After abba’s diagnosis, my brother called up all abba’s friends, or at least those still living, and asked them to visit him more often. Initially, they did, and then the visits petered out. The elderly are lonely, and men more so. Abba had a vibrant social life once, with uncles hanging out in our house daily. It was the equivalent of a bachelor pad, since my mother had passed away and my father hadn’t remarried. I made coffee for all the uncles, abba offered the cigarettes, and they chatted late into the night. I wonder what it would look like to design society in such a way that the elderly are treated with greater dignity. I read about Japan’s handling of its ever-increasing aging population and the Dutch village for people with dementia. It’s hard to imagine something like that in America, much less for the Bangladeshi community where the illness is not well-understood or spoken about.

- “Is this how you want to be spending all your time?” an aunt asks me after I WhatsApp her a portrait I’d finished. “Making art?” I play dumb because even before she confirms my suspicions, I know what she really means: Are you really wasting your time embroidering when you could be raising children or being married? This is not a new conversation. My life choices have all been weighed against my lack of a husband and children. At my lowest, I still embroider. I know that if I keep going, if I stitch a thousand stitches, then I’ll stop feeling the weight of depression and anxiety, that I’ll come back to myself. Her comments pull me down lower, and I try not to cry. I tell myself that her lack of appreciation for my art is because she’s limited in her imagination of how a woman can live her life. Her limitations are not my own.

- Sometimes, I spend hours embroidering in complete silence. This is usually in the mornings while I’m at abba’s and everyone is fast asleep. In those hours, I weave stories. In one I keep coming back to, I imagine a scientist spending all her time developing a device that will allow her to see the world as her spouse suffering from Alzheimer’s. She wants to join her wife’s reality, help her navigate the holes in her memory with the scientist’s own, creating a symbiotic relationship that keeps them both in reality and together longer. I read somewhere that Alzheimer’s is your brain turning into Swiss cheese. Watching abba through his dementia, I learned that the mind will make up stories to fill these gaps. I feel my own desperation through the scientist; the desire to take away a loved one’s pain.

- At my highest points, my heart sings with vision and purpose as I embroider. I imagine all the art I want to create, the stories I want to tell, the legacies I want to leave. I live in the thrill of each piece, diligently cataloging the ideas in a notebook. I imagine people consuming my art and feeling seen. And in these visions, I find hope, a precious gift in a time when grief overwhelms.

Fatema Haque is a Bangladeshi American writer, educator, and fiber artist based in Michigan. A self-taught fiber artist, Haque’s art celebrates the legacies of the Bangladeshi diaspora: those who immigrate and the memories they carry with them wherever they go. Her first solo exhibit, Bangladeshis in Michigan, will be on view from November 30 – December 20, 2023 at the Shapiro Library Gallery in Ann Arbor, MI. Follow her on Instagram or visit her website.

Read More

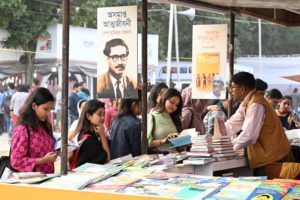

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More